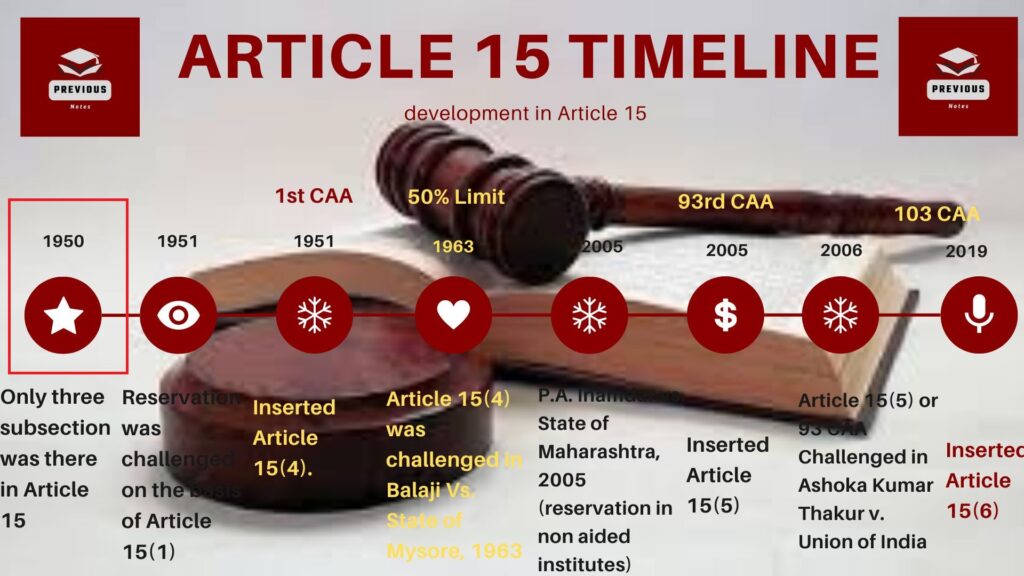

Article 15 of Indian Constitution:

Article 15 when Consitution was passed:

(1) The State shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them.

(2) No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them, be subject to any disability, liability, restriction or condition with regard to—

(a) access to shops, public restaurants, hotels and places of public entertainment; or

(b) The use of wells, tanks, bathing ghats, roads and places of public resort maintained wholly or partly out of State funds or dedicated to the use of the general public.

(3) Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any special provision for women and children.

State of Madras vs. Champakam Dorairajan 1051

This was the position of Article 15 when the constituion was passed, there were only three subsection in it. Then one case i.e. The State of Madras vs Champakam Dorairajan 1951 AIR 226, 1951 SCR 525 came into the picture, this is regarded as the 1st reservation case in the history of India.

Fact of this Case:

- a Brahmin woman from the state of Madras, was denied admittance to the medical school in 1951 despite her qualifications.

- This case was challenged on the ground that a women was denied admission in an educational ground. She filed the case on the ground that discrimination was done on the ground on caste and due to this Article 15 was infringed which says “the state shall shall not discriminate any citizen on ground only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them.”

- This was based on the Communal Government Order issued by the Province of Madras or Madras Presidency in 1927, just before independence (Communal G. O.)

- Madras state passed this order on the ground of Article 46 which says:

- Article 46: Promotion of educational and economic interests of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and other weaker sections The State shall promote with special care the educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people, and, in particular, of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation.

- Now, there is a conflict between Article 46 and Article 15 (1) or DPSP Vs. Fundamental Rights.

Court Decision:

Fundamental Rights are supreme. FR> DPSP.

To nullify the Court Order, 1st amendment was done which nullify the court order and Article 15(4) was inserted in the constitution of India.

(4) Nothing in this article or in clause (2) of article 29 shall prevent the State from making any special provision for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes.

Balaji Vs. State of Mysore, 1963

The case of Balaji vs. the State of Mysore, 1963, is a significant legal landmark in Indian constitutional law. This case challenged the validity of certain provisions of the Mysore government’s reservation policy.

Main Outcome of this Case:

- Validity of Article 15(4): The case primarily dealt with Article 15(4) of the Indian Constitution, which allows for special provisions for the advancement of socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

- 50% Ceiling Limit: The Supreme Court, in its judgment, upheld the validity of reservations but ruled that the reservation policy should not exceed 50% of the available seats. This ruling established the principle of a 50% ceiling on reservations, which has since become a guiding principle for reservation policies in India.

- Further Classification of Backward Classes?: It disallowed the further classification of backward classes.

- Identification of Castes: The court acknowledged that caste can be one of the factors in identifying backward classes, but it should not be the sole criterion. The court emphasized that backward classes should be identified on the basis of social and educational backwardness rather than caste alone.

Indira Sawhney Vs. Union of India, 1992

The case of Indira Sawhney vs. Union of India, 1992, is a landmark judgment by the Supreme Court of India regarding reservations in public employment and educational institutions. The case is commonly referred to as the “Mandal Commission case.”

Here are the key points and outcomes of the Indira Sawhney case:

Background:

In 1990, the then Prime Minister, V.P. Singh, implemented the recommendations of the Mandal Commission, which proposed 27% reservation for Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in civil services and public sector undertakings.

The implementation of these recommendations led to widespread protests and legal challenges, resulting in the Indira Sawhney case.

Key Issues:

The main issue before the Supreme Court was the constitutionality of providing reservations to OBCs in public employment and educational institutions.

The petitioners argued that the reservations violated the principle of equality under Article 14 of the Constitution and exceeded the 50% cap set by the Balaji case (Balaji vs. State of Mysore, 1963).

Supreme Court’s Decision:

The Supreme Court, in its judgment delivered on November 16, 1992, upheld the constitutional validity of reservations for OBCs.

The court ruled that social and educational backwardness, along with inadequacy of representation, could be valid criteria for providing reservations.

The 50% ceiling on reservations was reiterated, but the court also recognized exceptional circumstances where exceeding this limit might be justifiable.

The court directed the exclusion of the “creamy layer” within the OBCs from the benefits of reservations. The “creamy layer” refers to the relatively more affluent and advanced sections within the OBCs.

Impact:

The judgment had a significant impact on reservation policies in India, particularly for OBCs.

It clarified the legal framework for reservations and established the concept of the “creamy layer” exclusion.

The decision also led to further debates on the need for reservations, criteria for determining backwardness, and the overall social justice framework in India.

The Indira Sawhney case remains a crucial reference point in discussions on affirmative action and reservations in India.

To dilute the court decision in this case, below amendments were passed:

77 Amendment, 1995-This Act aimed at extending reservations for promotions in jobs for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (SCs and STs).

81st Constitutional Amendment Act, 2000: It introduced Article 16(4B), which says unfilled SC/ST quota of a particular year, when carried forward to the next year, will be treated separately and not clubbed with the regular vacancies of that year.

85th Constitutional Amendment Act, 2001: It provided for the reservation in promotion can be applied with ‘consequential seniority’ for the government servants belonging to the SCs and STs with retrospective effect from June 1995.

P.A. Inamdar vs. State of Maharashtra, 2005

Background: In 2002, the State of Maharashtra introduced the Maharashtra Unaided Private Professional Educational Institutions (Regulation of Admission to Full-Time Professional Undergraduate Medical and Dental Courses) Act. This law mandated a certain percentage of seats in private unaided medical and dental colleges to be reserved for students belonging to Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs).

Key Issues:

The main issue in the case was whether the state could impose reservations on private unaided educational institutions, particularly in the context of professional courses like medical and dental programs.

The petitioners, who were private unaided colleges, challenged the constitutional validity of the legislation, arguing that it violated their autonomy and fundamental rights.

Supreme Court’s Decision: The Supreme Court, in its judgment, upheld the constitutional validity of the legislation but with certain limitations. The key points of the judgment include:

Autonomy of Institutions: The court recognized the autonomy of private unaided educational institutions, stating that they have the right to administer their own affairs, including the right to admit students.

Regulation by the State: While acknowledging autonomy, the court also held that the state has the authority to regulate admissions to ensure that the admission process is fair, transparent, and based on merit.

Reasonable Restrictions: The court emphasized that any regulation imposed by the state should be reasonable and should not infringe upon the fundamental rights of the institutions.

Cap on Reservations: The court imposed a cap of 50% on reservations, stating that reservations should not exceed this limit in order to preserve merit.

No Quota for Minority Institutions: The court clarified that minority institutions, based on religion or language, are exempt from these regulations. They can admit students in a manner consistent with their minority status.

The P.A. Inamdar case established important principles regarding the balance between the autonomy of private unaided educational institutions and the state’s regulatory powers in the context of reservations in professional courses.

93rd Amendment Act:

To dilute the judgement, parliament passed the 93rd constitutional amendment, which states as under:

(5) Nothing in this article or in sub-clause (g) of clause (1) of article 19 shall prevent the State from making any special provision, by law, for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for the Scheduled Castes or the Scheduled Tribes in so far as such special provisions relate to their admission to educational institutions including private educational institutions, whether aided or unaided by the State, other than the minority educational institutions referred to in clause (1) of article 30.

(93rd Amendment Act of 2005)

The said amendment was challenged in Ashoka Kumar Thakur V UOI case but petition was rejected.

103 Amendment Act:

Recently in 2019, 10% reservation for EWS Category was granted which again crossed the ceiling limit decided by Hon’ble Supreme Court in Balaji & in Indira Sawhney Case. The matter regarding the same is under consideration.

Article 15(6)

6) Nothing in this article or sub-clause (g) of clause (1) of article 19 or clause (2) of article 29 shall prevent the State from making,—

(a) any special provision for the advancement of any economically weaker sections of citizens other than the classes mentioned in clauses (4) and (5); and

(b) any special provision for the advancement of any economically weaker sections of citizens other than the classes mentioned in clauses (4) and (5) in so far as such special provisions relate to their admission to educational institutions including private educational institutions, whether aided or unaided by the State, other than the minority educational institutions referred to in clause (1) of article 30, which in the case of reservation would be in addition to the existing reservations and subject to a maximum of ten per cent. of the total seats in each category.

(103rd Amendment Act of 2019)

Leave a Reply